Have you ever thought about change? No really, like, what is change? If you use the interwebs you find that there are thousands of organizations touting change. There’s Change.org, which advocates for certain political policies and attempts to influence American voters. There’s Make a Change Inc. that advocates for foster kids and Make A Change in the World that advocates for change by making powerful “microdocs”.

What’s a microdoc?

There’s Make A Change International which aims to change things like world hunger, and there’s makechange.net, which for some reason is an environmental media outlet that offers uplifting and inspirational stories about climate change. One of these change oriented organizations called WAN, or World Animal Net, describes what a social change movement is, and how it works. They proclaim, “Social movements like our own, develop because there is a perceived gap between the current ethics and aspirations of people and the present reality we experience.”

Change.

It’s hot.

But what is the New World philosophical take on change? Is it a good thing and why? How does it work? How should it work?

To answer, I’ve chosen to tell you a story.

Our story, which is a very true story, begins in a high school in Beijing in the 1960’s. The school, Tsinghua Middle School (in China a high school is called a middle school), had some very compelling students – kids who thought hard about life. One of these kids, a young man named Zhang Chengzhi (who incidentally would go on to convert to Islam and become one of China’s greatest writers), became rather upset at some articles in his neighborhood newspaper. The articles were critical of a very popular play, Hai Rui Dismissed from Office. It seems that for Zhang, the educated elite were too comfortable with the anti-Maoist sentiments in the play. The elite weren’t energetic enough and angry enough at the hidden bourgeois messages found in the production. So young Zhang started a school movement to expose the people whom he believed to be traitors to the principles of the communist revolution. The irony is he was exposing the very generation responsible for the revolution only 20 years before. This teenager was starting something that would change China forever.

Zhang called his movement and its followers the Red Guard, and the Red Guard began to publish, protest and march. In Beijing, school administrators started to push back. Who’s this kid calling out the heroes of the revolution, anyway? Administrators from the school began to refer to the Red Guard as counterrevolutionaries. At this time in China, the spring of 1966, a radical was one who supported bourgeois notions of freedom and small R republican-style democracy. Counterrevolutionaries were even worse. They were out to destroy the great Maoist revolution. Zhang and his high school cohorts were called both. They had put themselves in the crosshairs of the CPC, the Communist Party of China.

Or had they?

It turns out that Zhang and others like him, including a famous young female administrator at Peking University, Nie Yuanzi, had gotten the attention of Chairman Mao himself. Mao, of course, is the leader of all leaders, the father of the Chinese Communist Revolution, the one who got the whole ball of wax rolling in 1949. He rather enjoyed how the Red Guard attacked Chinese intellectuals as arrogant and old fashioned, and he loved the way the Red Guard accused their teachers and their parents of bourgeois tendencies.

A quick definition of bourgeois, shall we? In French, the term means, “those who live behind walls.” In revolutionary France and Russia and America too, the bourgeois were generally known as those who have property, a proper education and a general leg up when it comes to political influence. Think suburbia, if that helps.

Mao loved the Red Guard because they could be useful to him and his renewed attack on the bourgeois of China. Like young Zhang, Mao saw his revolution slowing down twenty years after it started. He, like the kids, thought the older generation had lost some love for the communist vision of a better life.

And that’s when Mao did something remarkable.

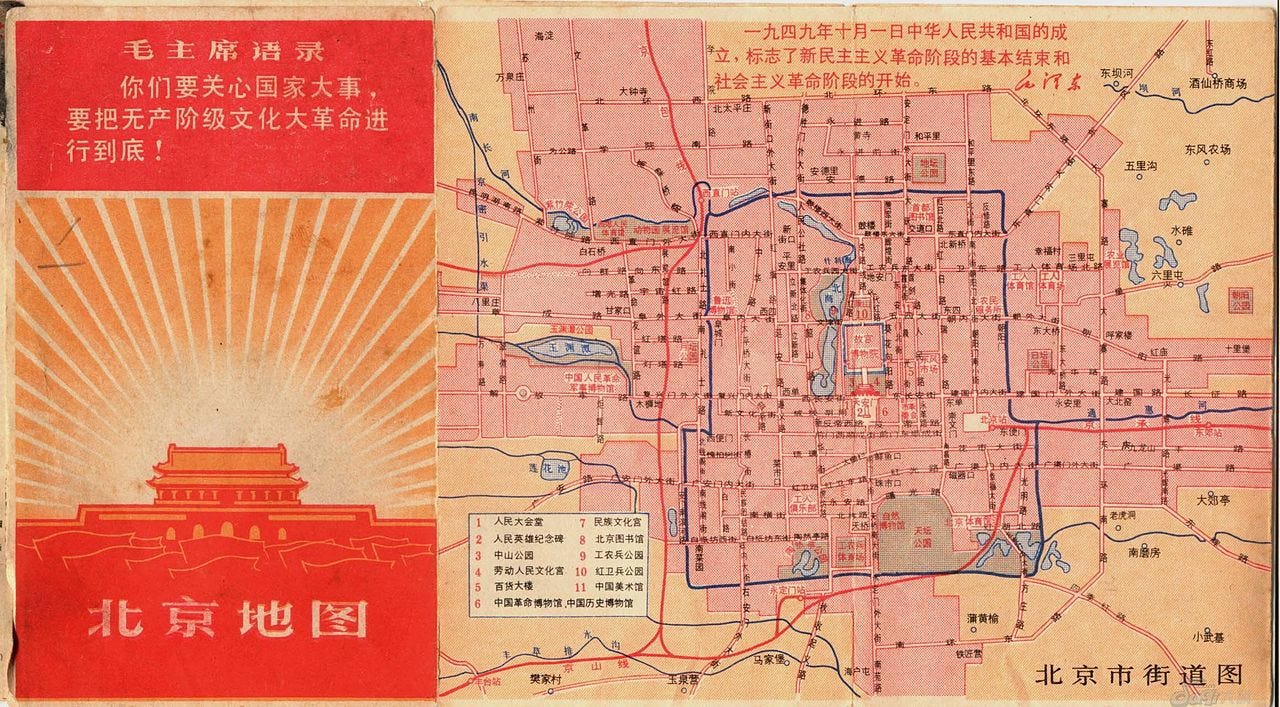

Mao got a copy of Zheng’s high school manifesto and broadcasted that teenage tome on national radio. In prime time. Next he called for a rally. The rally, famously dubbed “8-18” (it happened on the 18th of August), saw nearly 1 million young people congregate in Tiananmen Square. Mao appeared atop Tiananmen wearing an olive green military uniform, the type favored by those zit-faced Red Guards, and a style not donned since the defeat of the Chinese nationalists in the 1950s. From there, Mao personally called 1,500 ruddy-faced Red Guards to join him on the platform high above one million teeming teens, where Zhang, the high school kid who had started it all, placed a Red Guard armband on his beloved leader. Together, Chairman Mao and his new teeny bopper guard darlings, waved and applauded in front of the entire nation.

Mao had turned the little high school movement into a roiling force of nature, and with their energy, he would wage war on Confucian China.

Wait, Confucian China? In this Substack, Confucian China just means Old World China, the China of the Dynasties, the China of the Great Wall and of the Five Constants.

I love that name. The Five Constants.

Confucius taught a bunch about a bunch, but among his most vaunted teachings was that all the members of society must practice and pay homage to five eternal virtues, or what he called The Five Constants, or in Chinese: Wǔcháng (五常)

The Five Constants are:

Rén (仁, benevolence, humaneness);

Yì (义; 義, righteousness or justice);

Lǐ (礼; 禮, proper rite);

Zhì (智, knowledge);

Xìn (信, integrity).

Along with the Five Constants, Confucius taught that there existed a type of societal glue that could be identified in Five Bonds, or eternal hierarchies that every society should strive to maintain. Those five bonds, or relationships were:

FATHER - SON

A father must provide wisdom to the son, and the son must be obedient to the father.

HUSBAND - WIFE

A husband must protect and honor his wife, while the wife must obey her husband

OLDER BROTHER - YOUNGER BROTHER

An older sibling must create an example for the younger, but the younger must, you guessed it, obey his/her older sibling.

RULER - RULED

A ruler must have the tools of power and rule his subjects, but only if the ruler obeys the mandate of heaven and provides wisdom and guidance to his subjects. Subjects must obey their rulers.

FRIEND - FRIEND

This is the only relationship of the five built squarely on equality and an absence of obedience.

For Confucius, these relationships constituted a type of celestial order, a list born out of cosmic reality, a truth reflected in nature and written into the hearts of humankind. These things should not change. These things could not change if stability and human flourishing were a goal of society. Except for the mutual equality of the Friendship Bond, these teachings of Confucius were clearly at odds with the ideology of equality. They were clearly a sticky pot point of contention for Maoist ideology and Red Guard rage.

But for Confucians, still the majority of folks living in China in 1966, these profoundly old bonds weren’t ideologies. They weren’t thoughts in a man’s mind. These hierarchies were the same as water or food, given to humans so that they might live a good life.

But are they really like food and water? Are they eternal, good, forever? And if they aren’t, aren’t they just ways to control people? Ways to create inequality? And if that’s the case, shouldn’t the constants change?

This skeptical approach was the thinking of the Red Guards. This was the thinking of the French Revolutionaries, too. It was the thinking of the founding fathers here in the United States, even if our American founders had a more, shall we say, conservative version of the equality ideal.

And this equality equation was the new principle that Mao and his Red Guards set out to instill in every Chinese town in 1966.

Mao was coming to wreak havoc on the old ways.

The official persecution of old things had a not-so-catchy-name. Sweeping Away the Four Olds is what they called it. The four olds: old customs, old habits, old ideas and old culture. This type of political language appeared everywhere during the Cultural Revolution.

The vague nature of these terms allowed Red Guards to target all types of cultural icons. Confucius’ grave was torn up and vandalized. Red Guards dug up the burial site of the ancient Ming Dynasty and proceeded to desecrate and burn the skeletal remains of the Emperor and Empress Wanli. Family genealogy books, a tradition in Confucian China and well known to every Chinese family, were bound and burned by marauding Red Guards. Taoist temples and western-style Christian churches were plundered and destroyed. Parents were reported to authorities by their own Red Guard children. Everyone was forced to read something called the Little Red Book, a book of Mao’s most famous sayings. More than 280 million Little Red Books were published between 1966 and 1974, outpacing even the Bible as the world’s best seller.

Most interesting to me, as a former educator, is what took place in schools. In the summer of 1966, thousands of teachers were marched before their students and whipped with belts – by their students – for “backward” and bourgeois ideas. Many, many others, under threat of violence, were forced to prostrate themselves in front of their students, begging forgiveness. Many educators committed suicide after these events, lost in the shame of having been stripped of their Confucian honor. In Shanghai, more than 800 men and women killed themselves in just two months.

In what was now being called Red August, Mao issued a decree to Beijing policemen to “stop all interventions in the affairs of the Red Guard.” The leash had been loosened. By September, 1,700 Confucian elders were beaten to death at the hands of their progeny. Students clamored for a re-education program, and in turn, the CPC created re-education camps all across the provinces; places where parents and grandparents were sent to unlearn the Four Olds. For ten years, millions were re-programmed in the ways of New World China.

Change is cray cray!

And here’s when it really gets interesting. Here’s where we get back to our question about change. During all of this, throughout the melee and orgy of violence, the original student movement led by Zhang and his prodigious pals at Tsinghua Middle School, well, it began to fracture. Competing student groups began to argue over which group was most pure. A radical Red Guard group called Sheng Lu Wee started to attack the PLA, the People’s Liberation Army, and that was not a great idea. The PLA was the standing army that protected all Chinese legislators and the Politburo as a whole. Even Mao found this dangerous. And you guessed it, the Red Guard began to be seen as a threat. Mass executions of Red Guards took place in Guangxi province, and by 1969, the Red Guard was no longer a political force in China. In fact, some say as many as a million Red Guards had been executed by 1979.

Things had changed alright. This time, they had changed back.

The problem, of course, is that what is now new will soon be that which is old – a conundrum for people who want “change”. Change will come, but nothing new will remain as such, and in turn, the new will become useless and a target for destruction. Thus is evolution. Thus have we been taught in science class. All of the Light People revolutions are built on the evolutionary mindset, and in turn, all of them must succumb to their own ideology.

What does the Old World think of all this? Well, take a look at an old tradition we practice here at First Things Foundation. It’s called the Georgian Supra. You should do one soon, because, well, it’s a joy. Anyway, in the Supra there is always a toast to the dead, to the ancestors. Usually there is more than one, but without fail there will be one. And everyone participates. Men and women stand and member-again their loved ones in word, recalling the lessons taught by their lives, honoring their ancestors by calling back to them in name. You see, in Georgia, as in most Old World societies, the dead have the answers for what ails us. They hold the key to the future because what is coming will always resemble what has passed. Our sins, like our successes, don’t really change. That which is good (love, truth, honor, etc…) remains good from age to age, battling the forces of evil, which though appearing to change, also remain the same from age to age (pride, arrogance, greed, lust, etc…). The spirit of the dead offers the future to the young. But of course, in the Old World, the dead are not dead at all, but alive and well in the souls of the living. Which means that the living must lower themselves in obedience to the spirit of the dead. That which was now lives within that which is.

Paradox is hard.

These ideas about old things informing new things is an attack on the spirit of the New World, the spirit of utopia, of individualism and the worship of what comes next. The Old World reverence for ancestors is a major roadblock to New World freedom. After all, if the way to a good life is simply to obey the wisdom of elders, what is the point of my freedom and my choices and all that exists therein? Why must I have a master, if I can be my own?

Before I put my computer pen down, I want you to notice one thing about the story above, about the Red Guard. Did you notice how fast communist leaders moved to purify their ranks, not once but twice in three short years? Change happens very quickly in the modern age, especially compared to the expanse of human history. The technocracies around us are aware of this calculus. The governments that partner with them understand the DNA of change, they have fully imbibed the modern mind and our worship of “the new”. But that image is terrifying when you really think about it. The image, of course, resembles Babylon, a people clawing their way up a great tower, the leader getting near the top, but so fatigued by the climb that his competitor can catch him and pull him by the pant leg and throw him down into the abyss, asserting his own strength and ascendancy, all until the next man reaches the next pant leg and the moment of violent victory. This is the image of change in the political world of modernity. It’s the nature of change in the natural, animal, and plant world too. Or at least, in the world explained to us by modern Darwinian scientists. In the end, for most true modernists, our world is simply about becoming the tip of the spear, the latest, most essential version of human winning.

But for folks like Confucius, this way of thinking was deadly. For folks like the earliest Christians, change was not a good unless the change resulted in the union of Creator and creature. Change was mostly private and within, demonic if not disposed toward a transcendent reunion with all that ever was. With God.

Maybe that’s the nature of change. Maybe change is just returning. Maybe all change is pointless unless it leads back; back to something essential, back to what we’ve always been? That feels old to me. And that feels very different than the story of the Red Guard.

Change comes hard, light ir not.